Einstein and God

Einstein and God

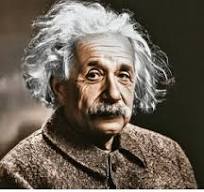

In the twilight of his illustrious career, Albert Einstein engaged in what would become one of his final recorded conversations, a poignant exchange that took place in 1954 with William Hermanns, a German American poet and scholar. This discussion, held not in the sterile confines of a studio but within the warm, intellectual sanctuary of Einstein’s Princeton home, was emblematic of the physicist’s enduring curiosity and philosophical depth. The presence of LIFE magazine editor William Miller and his son Pat, a Harvard freshman, added a familial dimension to the encounter, underscoring the informal yet profound nature of their dialogue.

The conversation was ostensibly casual, initiated by Miller’s desire for Einstein to provide guidance to his young son, who was wrestling with existential doubts and a burgeoning sense of nihilism about personal achievement. Yet, the topics broached during this meeting were anything but trivial, delving into the realms of curiosity, the meaning of life, the dichotomy between success and value, and Einstein’s personal views on religion and God.

Einstein, ever the inquisitive soul, questioned young Pat about whether the “undulation of light” sparked his curiosity, a query that served as a springboard into a deeper reflection on the nature of inquiry itself. Einstein famously remarked, “The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence.” He advocated for a daily contemplation of the universe’s mysteries, emphasizing the joy of gradual understanding over the conquest of complete knowledge. This perspective was not merely academic for Einstein; it was a way of life, a method of interacting with the world that maintained a “holy curiosity.”

Addressing the young man’s concerns about success, Einstein offered a counterintuitive perspective that remains resonant today: “Try not to become a man of success but rather try to become a man of value.” He critiqued the contemporary measure of success, which often values acquisition over contribution, suggesting instead that true value lies in generosity and the positive impact one has on others.

On the topic of religion and God, Einstein’s thoughts were clear and reflective of his lifelong skepticism towards organized religion. He expressed a preference for a cosmic religious feeling, one that transcends traditional doctrines and is rooted in awe at the universe’s law-bound beauty. His God was not one of intervention or moral judgment but one that existed in the harmony of the cosmos, governed by immutable laws rather than human desires.

This profound exchange was later immortalized in a tribute published by LIFE magazine shortly after Einstein’s death in April 1955, capturing the essence of his final year’s reflections. While the exact timing of this conversation remains slightly ambiguous in historical records, with some sources suggesting a date in late 1954 and others in early 1955, the content of their discussion is a testament to Einstein’s enduring intellectual legacy and his philosophical approach to life’s ultimate questions.

Though the 1954 conversation did not explicitly cover the concept of the afterlife, Einstein’s views on the subject were consistent with his broader philosophical stances. He was known to have rejected the notion of personal immortality, famously stating in another context that “one life is enough for me.” This aligns with his pantheistic view of the universe—a cosmos regulated by natural laws, devoid of supernatural rewards or punishments, reflecting a scientific spirituality that defined his personal and professional life.

Exploring the Depths of Curiosity and Awe in Einstein’s Philosophy

The internet is rife with content that claims to reveal the secrets of the universe, often using the allure of famous names like Albert Einstein to draw in viewers. These viral YouTube clips and social media posts typically present a mix of genuine Einstein quotes intertwined with fabricated elements, all designed to promote sensational theories about the afterlife. However, Einstein’s actual perspective was much more rational and grounded, showing a healthy skepticism rather than a penchant for drama.

Albert Einstein’s reflections on curiosity and “reverential awe” towards life’s mysteries offer a profound insight into his philosophical outlook, particularly in how he communicated complex ideas in a language influenced by his German roots. His discourse was not merely an exercise in philosophical musing but a deliberate attempt to mentor a young individual, Pat Miller, who at 19 felt disillusioned by the apparent pointlessness of science in a seemingly vast and indifferent universe. Einstein sought to shift this perspective, advocating for a sense of wonder as a guiding principle in life.

“The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence.”

This statement is a call to maintain one’s quest for knowledge and understanding, emphasizing that the act of questioning is an end, intrinsic to the human experience. It is not merely a tool for practical ends but a fundamental aspect of what it means to be human, akin to natural impulses like hunger or love.

“One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure of reality.”

Here, Einstein touches on the natural human reaction to the vast complexities of the universe. The scale of existence and the intricate laws governing life and reality evoke a deep, humbling sense of wonder, comparable to the awe one might feel when viewing a grand vista like the Grand Canyon.

“It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery each day.”

Einstein encourages a gradual approach to understanding the universe’s mysteries, advocating for small daily revelations as a means to stave off existential overwhelm and promote continuous, incremental learning.

“Never lose a holy curiosity.”

This plea highlights the sacredness of curiosity, urging us to preserve this quality against the cynicism and routine that often accompany adulthood. Einstein elevates curiosity to a divine status, intertwining it with his pantheistic view of God as the harmonious laws of the cosmos.

The Bigger Picture: The Genius of Einstein’s View on Curiosity

Einstein’s philosophy stands in stark contrast to the prevailing ‘hustle culture’ that values answers over questions. He champions a mode of being where curiosity is akin to reverence, transforming the pursuit of science—and life itself—into a form of worship devoid of traditional dogma. This perspective is not about solving mysteries but about allowing them to inspire and move us. In his later years, particularly after the ethical dilemmas posed by the Manhattan Project and the horrors of world wars, Einstein embraced this view as a means to find peace and wonder in the “marvelous structure” of the universe amidst chaos.

If Pat Miller’s story strikes a chord, it is because Einstein accurately identified a common human dilemma: our desire for certainty in a world where awe and wonder thrive on uncertainty. This approach encourages us to embrace the unknown with curiosity rather than immediate resolution, suggesting that the next time we encounter a simple mystery—like the purring of a cat or the bending of a rainbow—we should pause and ponder, allowing our “holy curiosity” to enrich our understanding of the world.